This second newsletter is all about data and assessment. When data became the buzzword in the late 1990s, we were all told to collect it, had no idea what to do with it, and mostly rejected what it was telling us with all sorts of excuses like “this assessment doesn’t reflect what my students can and can’t do!” Most of us carried on with what we were doing because we couldn’t see what it had to do with our teaching.

Things have changed; nowadays, more of us understand how data from assessments can change what we do in the classroom. We have a better grasp of formative assessment and a broader idea of data. Every chinning of a whiteboard provides us with data that can impact our next teaching decision. We don’t have to wait for assessment day. And…..finally, we have access to high-quality reading assessments that measure the right stuff and don’t waste student time or our time measuring reading disproven three cueing reading strategies. (RIP Running Records).

We hope you find these articles and new resources not only helpful but also reassuring. Playberry Laser aims to guide you and give you the support you need to use data more effectively to inform your teaching and optimise student progress.

Assessment: there’s tests and then there’s tests!

Tests come in two forms: criterion-referenced tests and norm-referenced tests. It is crucial for educators to grasp the difference and know how to utilize the results from each type effectively.

Criterion-Referenced Tests

Criterion-referenced tests are designed to measure mastery of a particular skill or set of skills according to some criteria. In literacy programs, these criteria are determined by what the program teaches – its own benchmarks. In other words, criterion-referenced tests measure a student’s performance against a fixed set of criteria or learning standards, determining what they can or cannot do. The Playberry-Laser spelling and decoding audits are criterion-referenced because they test what knowledge has been retained based on the criteria of what has been taught.

Criterion-Referenced results indicate:

- what we might need to re-teach the entire class (go back and reteach an entire week or a particular teaching point)

- what we need to increase the practice of (e.g., reintroduce particular cards to class decks, provide more spelling practice in words to spell or repeat a dictation, etc.)

- what we might need to reteach to individual students in intervention

This all comes under the banner of diagnostic teaching and formative assessment.

Norm-Referenced Tests

Norm-referenced tests are designed to establish a child’s skill level compared to those of the same age or grade across a population. Scores compare an individual student’s results against a norm group, ranking students to see where they stand relative to peers. DIBELS, PAT, The SA Spelling Test (Westwood) and the York Assessment of Reading Comprehension are examples of normed-referenced tests.

The norm (sample) group consists of a sample group of individuals of the exact same age who have sat the exact same same test. In educational research, a recommended norm group size typically ranges from 300 to 1,000 students. Their results are statistically analysed to create a distribution (bell curve).

“Norm-referenced tests compare a student’s performance (scores) to the scores of a group of people who were part of the sample used when the test was developed” (Farrall 2012:62)

Norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests are important for different reasons.

Criterion-referenced tests directly inform our teaching, letting us know what a student can and can’t do and what needs to be taught, practised more or retaught. They can inform whole class review cycles and intervention sessions. When formally reporting on student progress, we can use these results to a point, but criterion-referenced test results (like Playberry-Laser assessments) should never inform grades. Here, we must rely on norm-referenced results and our best interpretation of national curriculum assessment standards (which are pretty flaky in Australia).

Norm-referenced tests tell us how students track compared to a large sample (norm group) of students at the same age or grade level, which may make them more reliable when determining grades.

References:

Melissa Lee Farrall (2012). Reading assessment: linking language, literacy, and cognition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

The difference between assessing reading and spelling

“Our Dibels results show that the student’s reading is progressing, but the Playberry Laser spelling assessment shows that we have to take this student back.”

Playberry Laser uses a spelling (encoding) assessment for phase placement and progress monitoring. We chose spelling as the centre of our assessment because if a child can spell a word, they can read it in most cases. This means that students will be able to read words that they aren’t yet spelling, so spelling assessments are a very conservative measure of reading ability.

Assessing reading and spelling often yields different results due to the different cognitive processes and skills each task requires. Here’s a brief explanation of the key reasons:

Decoding (reading) vs Encoding (spelling)

Word Reading involves looking at letters or groups of letters and forming a mental pronunciation (decoding) to form a mental pronunciation, which triggers the word’s meaning.

Spelling involves mentally breaking a word down into its morphemes and phonemes, selecting the correct written symbols (encoding) for each, and then handwriting or typing the word.

Memory Use:

Word Reading relies more on recognition memory. Readers often recognise words by sight (for orthographically mapped words) or use their phonetic strategies to decode them.

Spelling relies more on recall memory. Spellers must correctly remember and apply specific letter combinations (orthographic representations), often without immediate visual cues. Spelling also relies on another bank of knowledge that goes far beyond just linking phonemes to their most common graphemes. Students must have an awareness of which graphemes spell which phonemes in different places in words. For instance, ‘ay’ spells long ‘a’ on the ends of base words like ‘play’, but not in the middle: ‘trayn’, and this then seems to break when we suffix the word ‘play’ to form ‘playing’ and all of a sudden, without an understanding that the ‘ay’ is not violating the ‘ay’ the end of a base word rule, it’s looks like it’s in the middle because of the suffix.

Phoneme Awareness:

Reading and spelling share a prerequisite of advanced phoneme awareness: the ability to quickly and easily identify and manipulate speech sounds in words. However, its application differs:

In Reading, phonological awareness helps decode words by linking sounds to letters. However, there’s more margin for error when reading. Say a student reads a word like ‘camel’ but misreads the first syllable as ‘came’ (mispronouncing the a as long (ā), thus getting an incorrect pronunciation for ‘camel’. This student can mentally check the words they know and conclude that they’ve certainly never heard of a (k)(ā)(m)(e)(l)! Then, this student can use ‘set for variability’ and mentally repronounce the vowel sound in the first syllable as short (ă). Immediately, this will trigger their meaning processor, and they’ll think, ‘Ah! Camel, that makes more sense! Set for variability is more commonly known as vowel stretching.

In Spelling, phoneme awareness helps encode sounds into corresponding letters and patterns. But it’s a much, much more precise game. Because our predecessors decided on only one spelling of every word, camel can only ever be spelt with that letter string (orthographic representation), and never kamel, kamal, kamol, kamil, camil … There’s just no wriggle room in spelling. We cannot rely on the reader to be able to decipher it. Spelling requires a deeper understanding and use of orthographic rules, including irregular spellings and exceptions, which can be more complex and less intuitive. And we all know that knowing a spelling rule and applying it consistently and automatically are two different things.

So in a knutchell…

Word Reading: Can tolerate some error if we don’t get the correct pronunciation at first read, or decode. Context often helps readers infer the correct word even if it’s partially misread. Set for variability allows us to stretch the pronunciation of a word until BINGO, it matches a word we know, and it fits.

Spelling: Pretty much has a zero-tolerance policy; incorrect spelling can change the meaning of a word or make it unrecognisable.

While word reading and spelling are interconnected skills, their different cognitive demands and how they are taught and practised lead to varying proficiency levels and, thus, different assessment outcomes.

Is spelling (encoding) a harsher measure of overall literacy progression than reading? Absolutely! Spelling is a hard task master. It places more demands on us than reading. However, it’s a highly reliable indicator of whether a student can read a word!

We have recently included decoding assessments up to the end of phase 2.

Schools need to be able to consider spelling and reading results when making sense of the results of all sorts of assessments, whether norm-referenced (like Dibels and PAT) or criterion-referenced, like the spelling assessments in Playberry-Laser.

You can’t beat diagnostic teaching

The Playberry Laser assessments are criterion-referenced, meaning they are diagnostic and inform what to practice more, what to reteach, and what to include in T2 intervention lessons. However, these results are only part of the picture .

The most effective form of criterion-based assessment teachers have is to watch student whiteboards and look at student books as they work. This on-the-spot, real-time data is precious. That’s where we see how a student is reading or spelling. We notice all sorts of things as we teach and make this easier for ourselves by strategically seating students so we can pay closer attention to the students we want to gather more data on (reds at the front, yellows and greens in the middle and blues furthest from us). Mind you, this type of ‘noticing’ takes practice and experience with your content. Less experienced teachers are more cognitively loaded with the task of teaching if the content isn’t automated for them. It’s easier diagnostically teach in a calm, well-routined classroom as well, so better classroom managers also have a clear advantage.

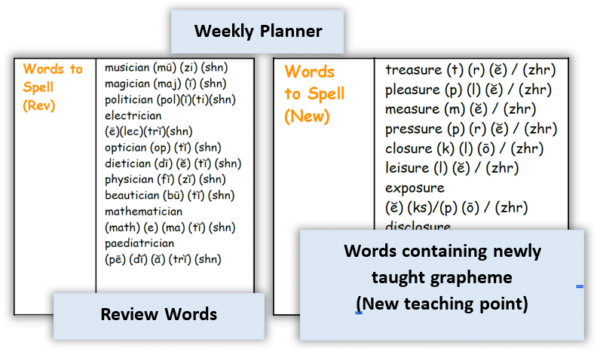

Making notes about what we’re seeing as we teach is crucial because we’re not going to remember everything we see whilst teaching. Patterns of performance can be quickly forgotten if a behavioural incident flares up or an annoying announcement blares through the PA. If we have notes on things several students did incorrectly, we can action them on tomorrow’s planner. In the example below, you can see that this teacher has noticed that several students are still shaky on some floss spellings as well as the dreaded (j) spellings on word endings and has decided to up the repetitions of these in the next lesson.

Although you can’t change the slides, and we certainly never want you skipping parts of the lessons, there’s plenty of scope for you to be responsive to assessment data in how you set up the reading and morphology card decks. As illustrated above, you can also decide to add or subtract words to spell and to add or subtract phonemes from the spelling review drill. Plenty of teachers also grab opportunities at other times in a school day to build in quick and lively bursts of review of concepts or graphemes that students need consolidated.

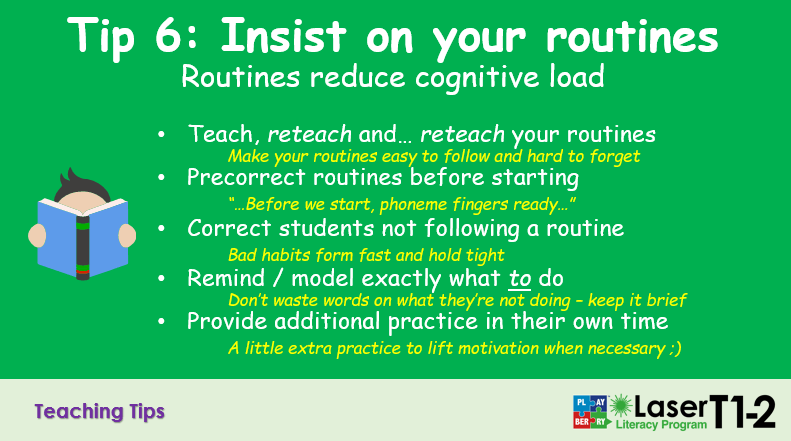

Diagnostic teaching is hard won. It takes experience with a program (you have to know the content well) and lessons must be orderly with students adhering to routines. This is why the hard graft of teaching, reteaching and insisting on routines, and never, ever dropping your standards is essential. It’s not easy but students always win when teachers maintain high standards.

New Assessment Documents on the Platform

Check out our new Assessments Overview and Assessment Schedule. These can be found in the resource section. Just select Assessments from the pull down menu. The Assessments Overview gives in depth information about the norm-based assessments we recommend and criterion-bases assessments we’ve build for you. The Assessment Schedule lays out all of the recommended assessments across the school year and how to collect and analyze the data. Tis is downloadable as a word document so your school can use it as a template for a working assessment document, adding to, or deleting from it.

Replacement morphology cards

Part of building a big program is making mistakes (embarrassingly). In morphology packs sold last year there are some incorrect cards that have since been rectified. The errors are in these cards.

suffix -er, (phase 2)

root -nov- (phase 6)

prefixes ex-, ef-, e- (phase 6)

root -graph- (phase 6)

root -gen- (phase 6)

If your cards are correct, they will look like the ones in the pictures above.

We’ve reprinted some card sets that can be collected from Fullarton House, otherwise, there’s always ‘the sharpie option’ where you make your own corrections.

Playberry Laser T1-2 is a teacher-supportive multisensory literacy resource for primary teachers to support their teaching in line with research. We’ve taken the planning and resource design load to free teachers to focus on building content knowledge and sharpening their delivery in line with Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction.