Multisensory Teaching and Learning: What is it all about and what is it not?

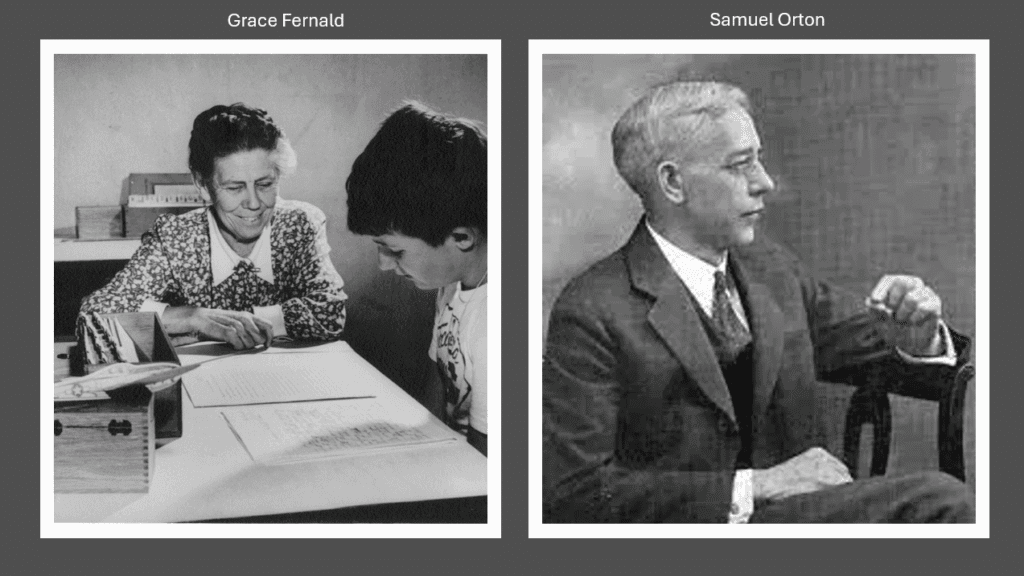

Multisensory learning as an instructional concept began in the early 20th century, primarily through the work of Dr Samuel Orton (the ‘O in ‘OG’) and Grace Fernald in the United States. Orton observed that many children with reading difficulties benefited from teaching methods that connected visual, auditory, and kinesthetic-tactile modalities at the same time. This approach became central to what is now known as multisensory teaching. Today, multisensory approaches are firmly grounded in structured, synthetic phonics-based reading and spelling programs, where they take their place within explicit, systematic phonics instruction to support attention and memory.

There is some nuance regarding which types of multisensory activities have an evidence base. Let’s begin with what many consider to be multisensory, but lacks supporting evidence. Current research does not appear to support large movements (known in the research as macro-level movements), such as sand tracing, writing in shaving cream, movement-based spelling, or moulding letters from clay. Air writing is even up for debate and is something we are closely examining at Playberry Laser, as it is currently included in the early phases.

Research suggests that the efficacy of Micro-level multisensory methods that focus on the small muscle movements of the vocal tract and hand. This instruction might include saying a sound, even watching the mouth in a mirror, paying attention to the placement of the lips and tongue when articulating a phoneme, and, of course, tying this in with the movement of the hand while writing its grapheme. More research is needed in this area.

What makes the spelling review drill multisensory?

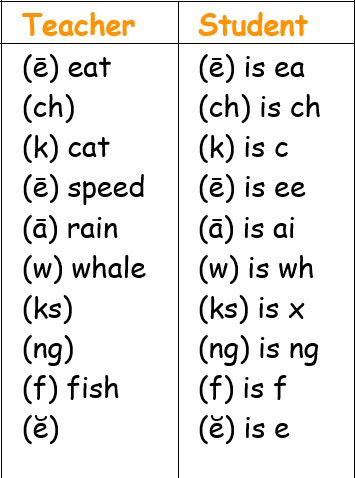

In Playberry T3 and Playberry Laser, Multisensory learning involves getting students to “say it, see it, hear it, and get it in the hand.” Let’s examine the spelling review routine and explore what makes it a micro-level multisensory approach. Look at the section of the teacher planner on the right. We’ve built this into the planner to guide you through the multisensory routine. Starting with the first phoneme at the top:

1. The teacher says the phoneme to the class – “(ē) like in eat‘”

2. The students repeat the phoneme, out loud, followed by the letter or letters (the grapheme) that spell the phoneme: “(ē) is ‘ea’“

3. As they say, (ē) is ‘ea’“, they’re writing the grapheme ‘ea’ on their whiteboards or in their books

The same routine then repeats for the phomeme (ch) and (k), like in ‘cat’ and so on.

What can be easily missed here is that the students are engaging their visual, auditory, and kinesthetic memory systems simultaneously.

Auditory: They hear their own voice saying “(ē) is ea”

Kinesthetic: They feel their hand from the letters ‘ea’

Visual: They see the letters forming as they write them

“So what? They say it, see it, hear it and feel it as they write the letters ‘ea’ … what’s the big deal?”

The big deal is that we have created neural connections in the brain between three memory networks –

- The network that has coded the visual image of the grapheme ‘ea’,

- The network that has coded the sound of both the phoneme of (ē) and the sound of saying the names of the letters that spell it – E and A, and

- The network that has coded the motor sequence of hand movements to create ‘ea’ in handwriting.

In the future, when this student is writing and mentally activates the phoneme of (ē) because they are spelling it in ‘eat’, the whole multisensory memory will activate together.

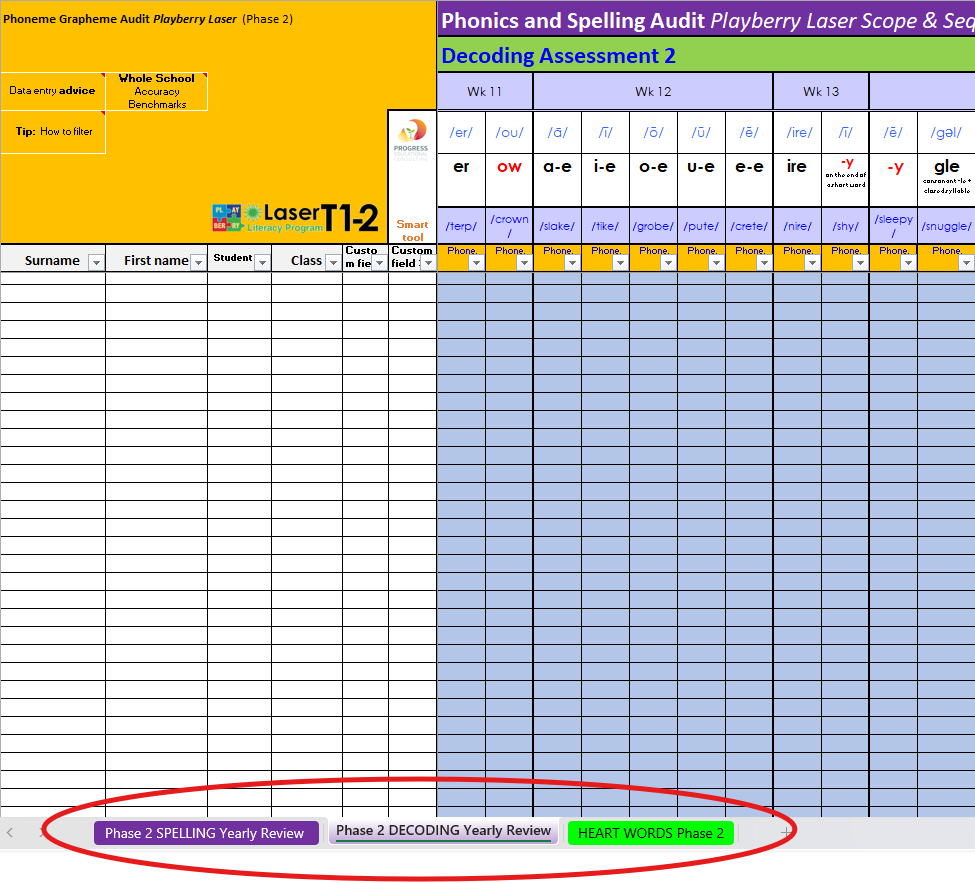

Report writing time approaches, and we need you to be crystal clear about which assessments you can report against and which assessments you must not report against

Assessments in education generally fall into two categories: criterion-referenced tests and norm-referenced tests. It is essential to understand these distinctions in order to select assessments that best serve both teaching and reporting purposes.Criterion-Referenced TestsCriterion-referenced tests measure a student’s mastery of specific skills or knowledge against fixed standards or criteria. In literacy programs, these criteria directly align with what the curriculum teaches in its scope and sequence. Such tests answer what students know and can do, without reference to their peers’ performance. The Playberry-Laser spelling and decoding audits are criterion-referenced because they assess retention against the content that was explicitly taught and guide teachers in identifying areas that require additional practice or re-teaching. Results from criterion-referenced assessments help educators to:

- Identify entire class concepts or weeks of content that may need a full reteach.

- Determine where additional practice is required, such as reintroducing spelling cards or repeating dictation activities.

- Pinpoint specific skills or knowledge to reteach for individual students during interventions.

These applications are central to diagnostic teaching and formative assessment, which guide instruction and targeted support.

Norm-Referenced Tests

Norm-referenced tests compare a child’s performance to that of a larger group of same-age or same-grade peers who have completed the same test. Examples include DIBELS, PAT, SA Spelling Test (Westwood), and the York Assessment of Reading Comprehension. In these assessments, scores position students relative to a norm group, often summarised as percentile ranks or scaled scores. Norm groups typically comprise 300-1,000 individuals, whose results are statistically analysed to establish distributions and rankings:

“Norm-referenced tests compare a student’s performance (scores) to the scores of a group of people who were part of the sample used when the test was developed” (Farrall, 2012:62).

Implications for Report Writing

Both types of tests serve important but distinct functions. Criterion-referenced assessments inform teaching directly, indicating which students need additional instruction or practice and supporting whole-class review cycles and interventions. However, while criterion-referenced results may support progress reporting, they are not appropriate for determining grades. For grading and benchmarking students against curriculum standards, norm-referenced test results and professional judgment, linked to national standards (ACARA), should be used—even though these standards may be inconsistent.Norm-referenced tests provide reliable information for grading by establishing a student’s relative position within a large, representative population. This makes them well-suited for formal reporting and comparison across broader educational contexts.

References:

- Farrall, M. L. (2012). Reading assessment: linking language, literacy, and cognition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Classtime. (2012). “Norm-Referenced vs. Criterion-Referenced Assessment.” Retrieved from https://www.classtime.com/en/norm-referenced-vs-criterion-referenced-assessment

- Renaissance. (2018). “What’s the difference? Criterion-referenced tests vs. norm-referenced tests.” Retrieved from https://www.renaissance.com/2018/07/11/blog-criterion-referenced-tests-norm-referenced-tests/

- Study.com. (2013). “Norm-Referenced Test vs. Criterion Referenced Test.” Retrieved from https://study.com/learn/lesson/norm-referenced-test-vs-criterion-referenced-test-what-is-a-norm-referenced-test.html

- Michigan Assessment Consortium. (n.d.). “Criterion- and norm-referenced score reporting.” Retrieved from https://www.michiganassessmentconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/LP_NORM-CRITERION.pdf

- NWEA. (2024). “Norm- vs. criterion-referenced in assessment: What you need to know.” Retrieved from https://www.nwea.org/blog/2024/norm-vs-criterion-referenced-in-assessment-what-you-need-to-know/

- Playberry Laser Program documentation and parent information. Available at:

Upcoming Tier 2 Training Days

The Playberry Laser Tier 2 training day is designed for teachers and support staff who use the Playberry Laser Tier 2 resources in their schools. Participants will learn how to deliver Tier 2 Intervention Lessons, assess progress, and access resources. The day also includes observing a demonstration lesson with students.

Participants must bring a mini whiteboard and a whiteboard marker.

Morning tea is provided. BYO Lunch.

9:00 am – 2:45 pm.

Upcoming Nuts and Bolts Training Days

If teachers aren't trained, they shouldn't be teaching Playberry-Laser Tier T1

We expect that all teachers teaching Playberry laser T1 have completed the Nuts and Bolts training day. Untrained teachers create all sorts of lethal mutations to the lessons and then wonder why they aren’t getting results. This isn’t deliberate; it’s what we do when we don’t know the correct way to teach something.

The Nuts & Bolts training day is for new teachers in existing Playberry Laser schools. We’ll get you started on the platform, teach you what you need to know to get started, and guide you through the essential instructional routines.

Participants must bring a mini whiteboard and a whiteboard marker.

Morning tea is provded and lunch is BYO.

Location of Training TBA

Arrive 8:45am

Need help making data-based decisions for 2026?

Data Analysis Sessions are designed for leaders to discuss and analyse their end-of-2025 Reading and Spelling Data with a Playberry Laser member. Schools that book will need to have their DIBELS and Playberry Laser Spelling Assessment data collated so that it can be discussed during this session. We will talk you through how to use this data to plan for 2026. Once you’ve booked, you’ll receive a Teams Invitation to attend the meeting.

Data Analysis Sessions Monday, December 1 & Tuesday, December 2, 2025

Bookable Timeslots – 9 am, 11 am & 1 pm

*Dates & Session times can be selected when checking out.

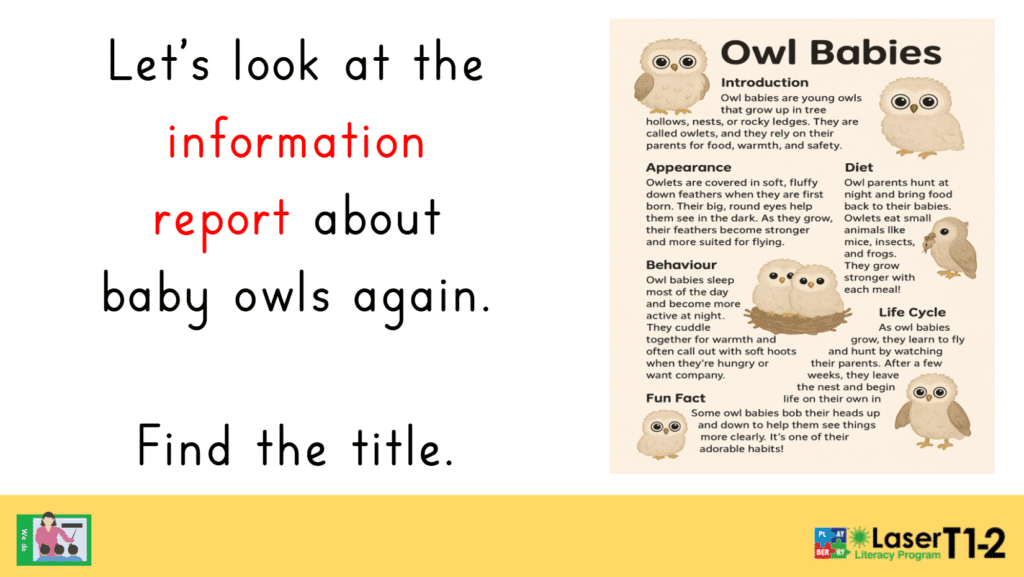

Year 1 Writing is now on the Platform

Year 1 structured writing lessons are now available on our platform. We believe we have found the ideal balance with our explicit, fine-grained writing instruction, drawing inspiration from a diverse selection of beloved texts such as Roald Dahl’s “Fantastic Mr Fox,” “The Three Billy Goats Gruff,” Margaret Wise Brown’s “Goodnight Moon,” and Michael Foreman’s “Dinosaurs and All That Rubbish.”

Each lesson is meticulously designed to combine the best features of explicit and direct teaching in structured writing. Teachers and students familiar with Playberry-Laser programs will appreciate the familiar frameworks and instructional routines integrated into the lessons.

Phase 7 has landed!

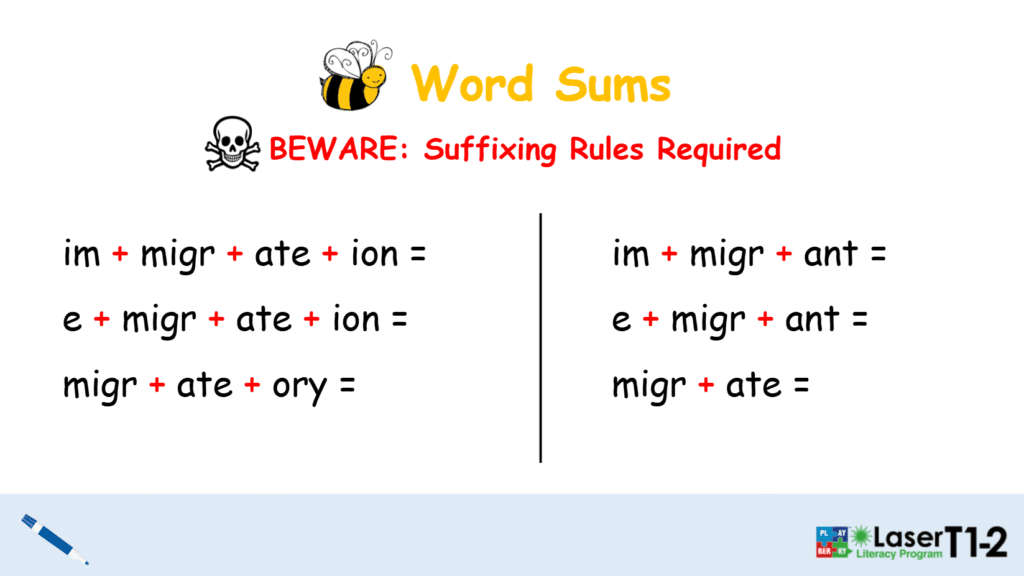

Playberry Laser Phase 7 is the final phase of the Playberry Laser literacy program. It emphasises advanced morphology, Tier 3 domain-specific vocabulary, and the consolidation of important morphological spelling rules, such as double consonants, dropping the ‘e’, and changing ‘y’ to ‘i’, as well as the appropriate use of connector vowels.

In Phase 7, students participate in three dedicated morphology lessons per week, which can extend into other subject areas, particularly science and mathematics, to strengthen their knowledge base. This phase reinforces and builds upon prior learning by focusing on less common spelling patterns and deepening understanding of advanced Latin and Greek morphemes.

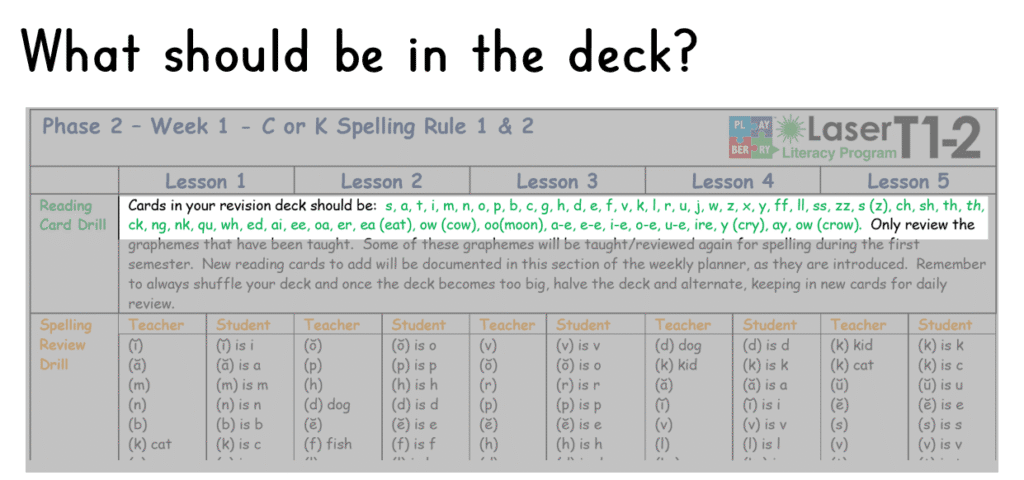

Keeping Reading Card Decks Tight and Tidy: Fundamental to your students' success

The weekly planner for Day 1 of Week 1 for each phase reminds you which cards should be included in the deck to start with (see the picture above).

You, of course, have discretion over which cards to keep in the deck, but the reading card deck should never have cards in the reading deck for GPCs that haven’t yet been taught.

Although you will have students who may know GPCs that haven’t been taught to the class, expecting the other students to know them violates a fundamental principle of structured literacy instruction. It’s a lethal mutation that disadvantages many students in your class.

Managing the reading card deck

When you teach a new GPC, the card for that GPC is added to the deck. Dah – you knew this already!

Each additional card makes the reading card deck fatter, and as you’re also aware, students will become so automatic in their recall of GPCs (cards) that you’ll soon ask yourself whether some cards need to stay in the deck.

So, the question begs: can you take cards out of the deck?

The answer: absolutely yes!

In saying this, we do want you to be mindful of a few things:

- Be sure all students are smashing out the card, including your less-able readers, these are your red and yellow DIBELS kids, and even some of the greens who may be only just green because of intervention. Remove cards based on the performance of your bottom end, not your top end. No student is ever harmed by being asked to practice something they can already do with ease. Overlearning has not yet harmed a student. AFL footballers can all kick a drop punt, but I’m yet to see a club remove kicking drills from training schedules.

- Single consonant graphemes that spell only one phoneme will probably be the fastest learned and likely the first you can trim from the deck – graphemes like ‘p’, ‘ t’, ‘n’, ‘f’ … you may ask, “Why not d ‘ and ‘b’? Because these are often confused for one another, particularly by some children with reading difficulties, I prefer to keep these in longer.

- Any consonant graphemes with more than one phoneme, like ‘s’ (with it’s (s) and (z) phonemes, and ‘c’ (with its (k) and (s) sounds) need lots of practice, so be careful about ditching these too quickly.

- Any graphemes connected to a spelling rule like –ck, -ll, -ss, -ff, -zz, -dge, -tch should be only removed when you’re really confident.

And of course, vowel graphemes – leave them in the longest. They are the most difficult because of their multiple phonemes. It’s the vowel graphemes that make English really complex orthography that it is, so these need the most practice, particularly by your most vulnerable readers.

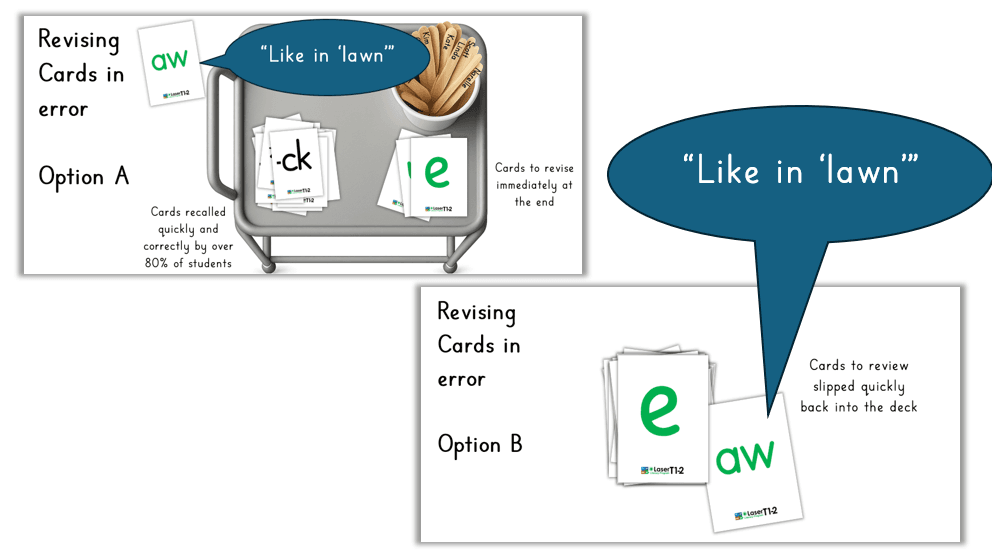

What do you do when the kids muck up a card during the reading card drill?

Do you plough on with the deck, ignoring the cards the students got wrong, or were slow in recalling? NO WAY.

It’s our job to teach responsively. There are a couple of ways we see teachers do this.

Option A is to put the card down into a different pile from the cards they recalled correctly, and go through that ‘error’ pack at the end. Say that several students say the phoneme (ŏ) for the ‘aw’ reading card. The teacher will cue the students, “like in ‘lawn’”, and immediately have the group repeat it correctly, then place the card on the revise pile.

Option B is to slip that card back into the back, about five cards back, so it comes up again soon.Take your pick, but Option B takes way more dexterity than Option A!

Get decks ready for the start of the school year

Your starting deck for the new school takes some preparation. If your students all come from one class, you can ask the previous teacher what their deck looked like. If you get your new class from a few different classes, then what goes into the reading deck may be a little more complex.

It’s not an exact science, and you may decide to begin with the recommended deck (as listed in the week 1 weekly planner). This will only work if you’re teaching from the beginning of a new phase (which we hope you will be). You’ll see how the class goes and add or delete cards based on the performance in the first few reading card drills.

What you do have to make sure of is that you have the cards you need and that class decks are complete and intact. This goes for morphology decks as well. Starting the new year with unchecked decks is a recipe for disaster. You want to have all of your materials organised so you can concentrate on getting students whipped into shape in terms of routines. Realising mid-lesson that you’re deck is missing cards will trash your lesson flow and get phonology off to an abysmal start.

Casualness leads to casualties – in this case, instructional casualties.

The first days of the school year are known as the establishment phase, during which you focus on routines and expectations and begin to build the classroom you want. If your teaching materials are ill-prepared, you’ll expend a lot of energy and frustration on this and risk losing your class early.