Bill and Christie-Lee Hansberry

Co-Directors Playberry Laser

Streaming has a dark past. In the 1950s and 1960s, IQ testing was used to organise (stream) students into set groups who would receive different academic programs from that point on. Groups in the upper stream would have access to highly academic content, the best teachers and even the best resources. At the same time, lower-streamed students could receive the opposite, which had a devastating and compounding impact on the futures of many. Like it or not, IQ tests have incredible predictive power for academic achievement, but they should never have been used in this limiting way.

Research in the 1960s and 1970s highlighted the obvious problems that resulted from IQ-based streaming. Educators became understandably wary of any deterministic practice that could lock students into an educational trajectory based on test results. The long-gone days of IQ streaming in schools casts a long shadow, causing apprehension among educators today about any form of ability grouping, and standardised testing for that matter. The Facebook feed of any educator is full of quotes hyperventilating about how ‘children aren’t test scores’. We agree, they are not.

Based on this, some schools take a no-ability-streaming stance, citing equity and inclusion, and claiming differentiation is the solution for addressing the needs of a class of students at vastly different ability levels. But how effective is differentiation in direct and explicit models or structured reading and spelling instruction? More on this later.

Instead of ‘streaming,’ we’ll use ‘ability grouping’ to distinguish it from the IQ-based streaming of the 1950s and 1960s. Ability grouping involves using data to form flexible groupings of learners, so teachers can target instruction to the group’s needs in front of them, teach responsively (check for understanding as they teach and reteach when needed) and monitor student progress more closely. The aim is to ensure that students are always in a group where the content is within their zone of proximal development. If you’ve picked up that we think this makes teachers more effective, you’re very intuitive.

Our short answer to whether ability grouping in structured reading and spelling instruction is appropriate is yes, but it’s not always necessary. To make our point, we will:

- Unpack why EDI’s assertion that all students should be taught at ‘grade level’ is practical in some subject areas, but breaks down in hierarchical subjects like reading, spelling and mathematics, where, ironically, explicit and direct methods of instruction work best

- Discuss differentiation within a structured spelling and reading lesson

- Dive into the nuances (when, why and how) of ability groups in reading and spelling instruction

All students at grade level?

We have much to thank EDI™ for. Explicit Direct Instruction is an incredible teaching model with roots deep in what we know from the science of how humans learn. We first encountered EDI™ during our visits to Bentleigh West Primary School, where we witnessed its use in structured literacy teaching firsthand. EDI™ (the book by Hollingworth and Ybarra) became compulsory reading for any educator visiting Bentleigh West on our many study tours there. EDI™ has changed the game.

The need for all students, regardless of ability, to be taught grade-level content is a principle that EDI™ strongly advocates. Its appeal to educators is understandable. It’s based on the notion that unless all students are given access to grade-level content, many will never catch up with their grade-level peers, remaining locked in below their grade level and permanently behind. EDI™ is reflecting educators’ historic concerns about streaming. EDI™ promotes differentiated, whole-class instruction with regular progress monitoring as the preferred approach to placing students into ability groups. We have a few issues with the notion that all students should be taught content at grade level and that differentiation is the answer. Let’s unpack this.

What is meant by at grade level when we talk about reading and spelling in Australian classrooms? Looking for answers in the Australian Curriculum has been an exercise in disappointment for many. A quick look sheds little light on reading and spelling achievement standards for Australian students from foundation to year six. A deep dive into the literacy learner progression offers some light, but it’s buried a long way down. Admittedly, we structured literacy folks are used to a high level of detail and are used to working with reading and spelling scopes, sequences, and aligned measurement tools that show us, with pinpoint precision, what students can and can’t yet do with our complex orthography. Our diagnostic fetish cannot be easily satisfied by ACARA!

Can the criterion-based assessment tools that come with structured literacy programs help where ACARA can’t? Let’s say we assess Mrs. Hansberry’s Year Four class using the spelling placement test in our program (Playberry Laser T1-2). Could we say that a single level reached by 80 per cent of students (as determined by the highest phase where 80 per cent of students can correctly spell using code at that level) accurately reflects ‘grade level’ achievement?’ What if in Mrs Clune’s Year Four class across the hall’s 80 per cent proficiency point is different to Hansberry’s class? Sigh, and it probably will be. Most of these students would begin in a different phase of our program.

Criterion-based assessments (in-program diagnostic/placement assessments) should never be used to establish what ‘at grade level’ is because they aren’t norm-referenced.

The concept of ‘at-grade level’ in reading and spelling is hard to pin down. For the schools we work with Dibels™ composite scores are the closest thing they have to knowing if a student is at grade level (but only in reading). But if two-thirds of Mrs Hansberry’s year fours are in the red for Dibels™ and two-thirds of Mrs Clune’s are in the green and blue, what does this mean for what Mrs Hansberry does with her class? ‘At year level’ is irrelevant, Mrs Hansberry and supporting intervention teachers have to do something to get each of those students’ reading and spelling moving. Picking an at-grade-level point and suddenly expecting all students to read words and passages (as well as write) using words at that grade level is crazy. As Seidenberg (2017) points out, “Children vary in how rapidly they progress along the path to reading, but there is little skipping ahead because the basic skills are prerequisites for more advanced ones” (2017:105). If we accept that reading development follows a developmental trajectory (as we should if we follow the research), it follows that differentiation will not cause any magic developmental skipping, no matter how much we want all students to be reading on grade level.

We don’t want to criticise EDI™. It has changed the game, and we actively promote it in Playberry Laser T1-2. However, we do want to highlight the difficulties of applying the ‘all students at grade level’ principle to structured reading and spelling instruction when it is used as an argument against ability grouping, particularly when a school begins the mammoth task of cleaning up its teaching of reading and spelling.

Differentiation?

Let’s put aside the elusive ‘at-grade level’ business and discuss something we see often when examining a school’s data from our program’s placement (onboarding) spelling assessment. We use spelling data because if students can spell a word, they can nearly always read it. In primary classes (years 3-6), it’s normal to see a spread of spelling ability that sends a shiver up the spine of most teachers. “How am I supposed to pick a point (at grade level) in the scope and sequence to teach across an ability range where one-third of the class is still blending CCVC words, another third is still mastering split digraphs, and the top third has mastered complex code and should be onto high-end Greek and Latin roots?”.

This teacher’s concerns are valid. It’s understandable that if a non-classroom-based colleague or so-called expert says, “You’ll need to differentiate instruction,” the teacher will look for the nearest sharp object! We would, too. We think we’ve found a strong correlation between the number of years out of the classroom and the number of times an educator uses the word ‘differentiation’.

The constraints on a teacher’s working memory make it impossible to effectively differentiate reading and spelling instruction across a wide ability spread. How does a teacher activate prior knowledge at multiple levels for all students and check for understanding as they teach? Can you imagine checking student whiteboards for three different things at once? Not to mention finding time within one lesson to review and effectively teach three different sets of content! None of this is possible with one teacher with one brain and 25+ students. When groups have students of similar ability, these problems are significantly reduced.

Not long ago, in most Australian classrooms, literacy lessons centred around providing different lists of words to different groups of students (often named after Australian native animals), who would toddle off to (hopefully) work independently on various (often questionable) activities to learn how to spell those particular words. Tell us this isn’t a form of ability grouping. The spelling test was on Friday. Compared to the research-based direct instruction methods used in structured literacy, teachers were much less active in these lessons and far less diagnostic in their teaching (not a student whiteboard in sight). The point we’re making here is that this differentiated word list approach saw teachers working completely differently to the fast-paced, diagnostic, high student response rates pedagogy that comes with explicit and direct reading and spelling instruction. When the teacher sent the Koalas, Emus, and Hairy-Nosed Wombats with their word lists, differentiation was far easier (but in no way effective) because the teacher’s role was different. Many argue that this differentiated word list teaching model was, in fact, not teaching at all.

Differentiation is much more effective in structured literacy lessons if students’ abilities fall across a narrow range. We would argue that classes with a wide spread of reading and spelling proficiency should be ability-grouped because it makes responsive and diagnostic teaching more achievable. Examples of appropriate differentiation within ability grouped lessons can include seating the students with the lowest ability closer to the front, so teachers can more readily check written responses (in books or on mini whiteboards) and provide faster and more frequent corrective feedback, tweaking dictation sentences for students who are less proficient with spelling, thus writing more slowly; or provide extension activities to lesson segments to extend the higher-end students. The Playberry Laser Teacher manual provides differentiation ideas that can be used with any structured literacy program. To get back to our point, differentiation in reading and spelling instruction works within a narrow ability spread. It is ineffective in groups with a wide ability spread because its demands exceed the cognitive resources of any teacher if that teacher is to teach explicitly, directly and responsively.

We don’t want to be misunderstood. Differentiation works well in subjects like HASS, where a teacher might provide a stimulus passage containing at-grade-level concepts and ideas to students at multiple reading ability levels for independent reading. The more complex text, with focus vocabulary, can be chorally read so that struggling readers hear the complex words read aloud by more competent readers. For written summative assessments, work can be created by some students from scratch in essay form, some students will use voice-to-text, while others can demonstrate their understanding orally. In this case, differentiation achieves its goal of allowing all students to access and be assessed on grade-level content.

Response to Intervention

Let’s consider the critical Response to Intervention (RTI) model, which falls under the umbrella of Multiple Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS). RTI emerged in the early 2000s as part of a broader effort to improve how schools identified and supported students with learning difficulties, especially reading disabilities.

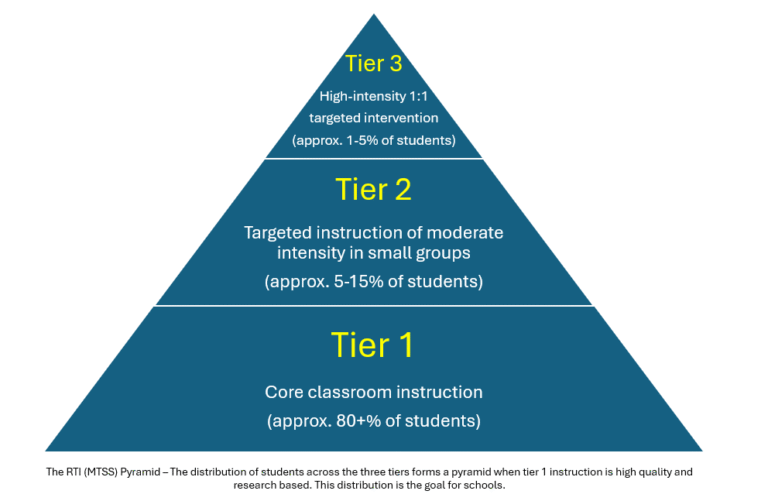

Most iterations of RTI present a three (multi-tiered system of supports MTSS), which is most often visually represented as a pyramid made of three layers or tiers. Each tier (going from bottom to top) represents a level of instruction for students that increases in frequency, intensity and specialisation. The pyramid shape of RTI reflects a distribution of students in any population who will progress satisfactorily with standard classroom instruction (Tier 1), those who will need additional, targeted small-group instruction (intervention) to keep up (Tier 2), and students who will need many hours a week of intensive one-to-one intervention to make even modest progress in reading (Tier 3). The triangle represents the prevalence and severity of reading disorders in any population.

It’s important to understand that the learned folks who first conceptualised the RTI pyramid weren’t talking about just any reading instruction at these three tiers; they had a very high bar in mind.

“The RTI classroom… would reflect high-quality, research-based instruction and behavioural supports, collaboration amongst professionals, and ongoing monitoring of student progress. Every aspect of instruction and every tool for progress monitoring was to be executed with fidelity; not only would educators be required to ensure that teaching methods were research-based, they would also be charged with ensuring appropriate student groupings and a scientifically determined instructional dosage” (Farrall 2012:104)

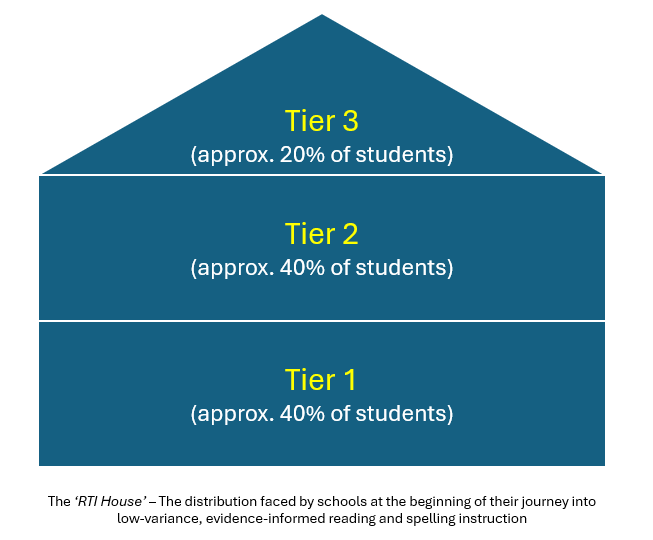

In our experience with schools moving into structured literacy pedagogy for the first time, they don’t have a pyramid but a house-shaped distribution. Every school that’s come on with our program (Playberry Laser T1-2) has started with a house. After an initial analysis of Dibels™ results, one local principal exasperatedly said, “We could have half our students in intervention!” Take a few moments to compare the percentages of students in the tiers of the pyramid and the house.

The reasons for a house-shaped distribution can sometimes reflect an unusually high proportion of reading/spelling disorders (specific learning disabilities / intellectual disabilities) within a student cohort. Most of the time, a house-shaped distribution shows that the classroom instruction at tier one has not been evidence-informed, taught well, taught enough, or all of these combined. In other words, reading and spelling instruction for these students has been loose since this cohort started school and has produced many instructional casualties. These students would not need intervention if the classroom teaching had met the standards outlined by Farrall (above).

As confronting as this initial data is for these schools, they need to make resourcing decisions about how to best target classroom instruction (tier 1) and best direct available intervention resources to get all students’ reading and spelling results moving- those with learning disorders (suspected or diagnosed), and the instructional casualties.

We encourage schools using our program to triangulate Dibels™ data, our placement spelling assessment and norm-referenced spelling data (e.g. Westwood’s South Australian Spelling Test), to help them decide on the starting points for all of their students on our scope and sequence. When analysing this data by class or cohort, teachers often face a spread of abilities that makes targeted instruction in standard class groupings a pipe dream and effective differentiation impossible. Faced with this dilemma, the first thought is to expand withdrawal (tier 2) intervention groups to deal with the large numbers of students who need to be brought up to speed. Still, teachers and leaders soon realise the number of students needing Tier 2 intervention is too great, as in the example above, where the principal acknowledged that they could have half their students in intervention.

Ability grouping is a practical solution for schools in the initial, messy (house) stages of implementing a high-quality, structured classroom reading and spelling program. It allows teachers to target instruction at the needs of their group and, since they do not have to provide the group with content at multiple levels, frees teachers’ working memory to watch students’ performance more closely as they teach. This makes teaching more responsive and effective. It makes teachers better.

For groups working at lower points of a program’s scope and sequence, the instruction can be seen as a form of daily tier two intervention. This isn’t a stretch when you consider that a primary goal of any intervention is to provide instruction targeted to the needs of students. We’re not saying this negates the need for small, withdrawal tier two intervention groups; they are essential for many students. We believe that ability grouping can increase the dosage of targeted teaching that the more vulnerable readers and spellers need. We have to talk about dosage. Your groups working at the lower levels will need more instruction and more practice opportunities. Lacking this increased instructional dosage, the gap between them and the other groupings will not close. We are, my friends, in the business of closing gaps when we intervene.

In addition to increased instructional dosage, ability grouping must, must, must be accompanied by ongoing and frequent progress monitoring so that students can move up groups when they are ready. We cannot stress this enough. Without data-informed mobility between ability groups, we end up with what we all fear—students forever locked below their potential. The Sold A Story Podcast (episode 11 – The Outlier) talks about Steubenville Elementary, a US school that uses ability grouping for reading instruction with excellent results. We strongly recommend listening to this episode as it goes right to the heart of this issue around three-quarters of the way in. Spoiler alert – progress monitoring is the secret sauce, along with high intervention dosages.

We do not suggest that all schools group students by ability when implementing a new reading and spelling program. Some schools may be so well resourced that they can provide withdrawal intervention to all students (reading/spelling disordered or instructional casualties) without robbing time from other lessons and subject areas. An analysis of some classes’ initial data shows that the majority of students are at the same point in the program’s scope and sequence, whatever that level may be (except a small, expected group of students already in intervention), so that the whole class can begin at the same point without the need to be ability grouped.

Ability grouping isn’t forever.

It is an approach used when necessary. Whether to group by ability always depends on the data. Some of our schools group their year levels, while others do not, for various reasons; again, it’s all based on data. The need for ability grouping is greatest in the first few years (the messy ‘house’ phase) of implementing a high-quality program, with fidelity. The need for ability grouping diminishes over the next few years, as ‘cohort zero’, the group who started school in the first year of our program’s implementation (who’ve received high-quality instruction from the beginning of their schooling), moves up.

Grade levels and older cohorts, with their higher number of instructional casualties, move on to secondary school. Over time, the distribution of students across the RTI tiers more closely resembles the pyramid. If it isn’t in any cohort, literacy leaders should look into the teaching and increase their support for the teacher(s) in the cohort.

We think we have made our point!

Ability grouping has a bad reputation, thanks to the ghosts of IQ streaming past. However, our experience, supported by a review of research, reveals no evidence that ability grouping is harmful in the context of reading and spelling instruction. We hope this post has made a clear and compelling case for when and why ability grouping can be appropriate and essential.

Unfortunately, appealing statements such as ‘all students at grade level’ are often too broadly applied in education, and in the case of reading and spelling instruction, without considering the hierarchy of skills that can’t be shortcut. Students must be taught explicitly within a structured program within their zone of proximal development. Too often, teachers are asked to differentiate across a range of abilities that is too wide to teach effectively, and in these cases, ability grouping is appropriate. We must stress that this must be accompanied by ongoing progress monitoring where students are moved appropriately, not locked into instructional groups that are exceeded by their developing abilities.

Ability grouping is not always necessary, but it plays a vital role in reading and spelling instruction, especially in the early phases of a school’s change to evidence-informed teaching methodologies and when dealing with the casualties of less effective past instruction.

References

Hollingsworth, J. and Ybarra, S. (2018). Explicit direct instruction (EDI): the power of the well-crafted, well-taught lesson. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin Press; Fowler, CA.

Apmreports.org. (2025). Transcript of Sold a Story E11: The Outlier. [online] Available at: https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2025/02/20/sold-a-story-e11-the-outlier.

Melissa Lee Farrall (2012). Reading assessment: linking language, literacy, and cognition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley And Sons, Inc.

Seidenberg, M.S. (2018). Language at the speed of sight : how we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it. New York, Ny: Basic Books, An Imprint Of Perseus Books.